This week was marked by a moving evening event. Even if it wasn’t public at all. We were sitting with Pierre Burgauer and a little group of enthusiastic friends of the Jewish Museum Hohenems in the “Schlössli” in St. Gallen. Built in 1586 by Laurenz Zollikofer, a notable of St. Gallen and grandson of a leader of the Protestant reform in the city, the proud mansion today hosts a cosy restaurant. But we didn’t come for the food (even if the canapés served after our meeting were great. Thanks Pierre!).

What brought us together was the first session of a newly created foundation that shall support the museum, the initiative of Pierre and his family.

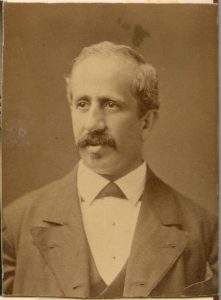

Exactly 140 years ago the Burgauers were the first Jews in St. Gallen who were granted citizenship in 1876. And while we expected serious business, coming together in the “Schlössli” with two well known lawyers and a financial expert, Pierre – with his wonderful humor – welcomed us with a protocol from 1860. On March 15, 1860 to be precise the council of the city of St. Gallen formally accepted the application of merchant Adolf Burgauer from Hohenems, his great-grandfather, to obtain the right to live in a private house and to have a stock of goods there for his trade. The positive decision was spiced with a few cautious remarks: Adolf Burgauer was informed not to host other Jews in his house and to be aware that this concession could be removed at any time and without conditions. A dry beginning of a great story. And a poignant beginning of a great evening. We hope we can report on this foundation soon. Our meeting at least was spiced with humor and heartfelt appreciation.

For today its time to look back into the Burgauer story. And you can find more about it in the newsletter of the American Friends of the Jewish Museum Hohenems and on the website of the Museum. But first let’s have a closer look on what has driven the Burgauer family history.

The Burgauer family first appeared in Hohenems in 1741, when Judith Burgauer, a young widow of twenty one and mother, grown up in the Burgau region near Augsburg, settled in Hohenems to marry for a second time. Jonathan Maier Uffenheimer from Innsbruck was a wealthy merchant and gave her a chance to begin a new life. And to have many more children. At least one child died young and there might have been more. A common fate at that time. But the others were better off. Their son Abraham married 15 year old Sara Brettauer from Hohenems and moved to Venice. Another daughter, Brendel, married Sara’s brother, Herz Lämle, later the patriarch of the Brettauer family and founder of the first banking business in Vorarlberg. Their daughters, Klara and Rebeka also married into successful families, the Viennese Wertheimstein and the Frankfurt Wetzlar family. Another daughter, Judith, married Nathan Elias, the head of the Hohenems community around 1800. This was a successful marriage policy and rather typical for a Jewish family at the upper end of the social hierarchy of the community. However, most of the Jewish families in that era had a hard time instead finding marriage partners and places for their children to settle and to make a living against all odds.

Of interest is what happened to Benjamin, Judith’s first son from Burgau. The sources as to when he definitely settled in Hohenems as well are scarce. Aron Tänzer mentions the year 1773, so it is possible that he grew up with relatives in the vicinity of Augsburg. In any case, sometime before 1772 already Benjamin Burgauer married Jeanette Moos, the daughter of Maier Moos, who for more then 20 years had served as head and representative of the Hohenems Jewish community. These were critical times; the family of the imperial counts of Hohenems died out and the countship fell back into the control of the Hapsburg Empire. Under difficult circumstances, new letters of protection needed to be settled. The Empress Maria-Theresa was known for her blatant anti-Jewish sentiments.

Even though Benjamin’s father–in-law successfully secured the future of the community and even though the dream of building a proudly visible synagogue took place while he was head of the kehillah, the community still had to survive restrictions and hardships. In the year of Maier Moos’ death, a great fire destroyed both half the Christian’s lane and the Jew’s lane. While the Jews were required to contribute financially to the reconstruction of the Christian quarter, support in the other direction was scarce. And the restrictions on settlement and marriage imposed on the Jewish communities, limiting the continuation of a family in Hohenems to one (and mostly the eldest) son and his offspring, continued until the middle of the 19th century. These restrictions forced the vast majority of children to emigrate, if they wanted to marry and create a family.

Two of Benjamin’s daughters, Esther and Brendel, found husbands in Lengnau in Switzerland. Brendel married Baruch Guggenheim,on e of the many Burgauer-Guggenheim connections that were to come. His son Benjamin Maier stayed in Hohenems, but three of his other children started business in St. Gallen and moved their families to the vibrant hub of textile production. Two other children emigrated in the 1840s and 1850s to the United States of America, particularly to Philadelphia, as did so many other of their fellow Hohenemsers. Family members of subsequent generations continued this migration, even from St. Gallen. And in South America, too, there is a Burgauer line today.

Thanks to Stefan Weis’ study „Entirely Unbeknown to His Homeland- The Burgauers. History and Migrations of a Jewish Family from the mid-18th until the mid-20th Century“, written as a diploma thesis in 2013, today we know much more about the origins, migrations, and diversity of the Burgauer family. With a generous grant from the American Friends Jewish Museum Hohenems – made possible by the efforts of the Leland Foundation, supported by Jacqueline Burgauer-Leland and Marc Leland – we were able to produce an English translation of Stefan Weis’ book. Have a look on the chapter on the Burgauers in the Americas in the Newsletter of the American Friends (http://www.jm-hohenems.at/en/about/friends/american-friends) or go for the whole book on our website (http://www.jm-hohenems.at/publikationen/downloads). Enjoy.

Excellent piece of writing. Thank you fro your clarity.

I feel very proud! Thanks a lot.

So proud and honoured! Thank you all for your generous support – Leland Foundation, Jacqueline and Marc, AFJMH, Pierre, Hanno and everybody I forget to mention…!

I know, not that easy to read as a novel – but I hope you enjoy discovering some maybe new facts of your roots.