Last weekend, I traveled to the Diaspora of Hohenems exhibitions. “Family Affair,” our show about the diversity of Israeli families, including the whole range of Jewish immigrants, Muslim and Christian Arabs and foreign workers—all those who form this fragmented society, is now being shown at the concentration camp memorial of Flossenbürg. A weird location one would say. Reli and Avner Avrahami, the artists, and Avraham Burg, the former speaker of the Israeli Knesset, came from Tel Aviv and Jerusalem for the opening. Burg expressed his puzzled feelings about his own presence on this site. He does not like the shoah business, the attempt to make the suffering and the annihilation of masses a subject of education and representation, esthetics and political interests.

But the Flossenbürg camp, once situated in the woods next to a village and a castle at the German-Czech border (and to a quarry the prisoners were forced to exploit) now offers all these contradictions as a starting point for a discourse about the present and the future. Even the history of the camp site after 1945 is discussed at length: the puzzling effect of turning such a site into a beautiful cemetery (already in 1947 by survivors and Polish DPs), a new suburbian housing project for German refugees from the East (in 1958), a park (administered by the Bavarian office for the preservation), a modern education center (since the 1990s), and even a “museum’s cafe” (in the old SS casino, now run by a integration project for young people with special needs).

For me and my wife, meeting our friends Reli, Avner and Avrum was a family affair in a disturbing setting, but also a heartfelt one. We did not present our reality of societies formed by intercultural exchange, migration, and the competition for legitimate identities, resources and power at such a place before. And that makes this playful exhibition, the family portraits and fragmented stories told by average people from all “tribes” all the more meaningful.

But this trip to the North-East end of Bavaria—the region is called Oberpfalz (Upper Palatinum)—was a family affair for me in a more profound way. The earliest Loewys in my family lived in two small villages on the Bohemian side of the border, Dlouhy Ujezd and Porejov. I found it difficult to pronounce these names when I was speaking to the audience that came to the opening in Flossenbürg… One of these villages—Porejov—was wiped out after the war, when American tanks liberated the area, and a year later the “German” villagers were forced to leave by the Czechs and became refugees in Western Germany. There is not much left of Porejov, but a ruined church and the Jewish cemetery, situated a few hundred meters away in the forests.

My ancestors in these villages were in cattle trade, and one of them, my great-grandfather made it to the “West,” which for him meant ten kilometers into the Oberpfalz, to Waidhaus, where he lived in a nice house that is still standing on main street. There, he did not sell only cattle anymore, but also the equipment for butchers.

Today, my greatmother and my young grandfather no longer stand in front of the house, but there is a signpost directing tourists to the memorial of Flossenbürg.

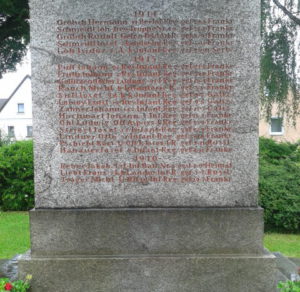

I had been here once previously, 36 years ago, with my father on memory lane, or better on the traces of memories we both never had. What struck me most when I went there with my father was the World War I memorial in the center of Waidhaus. With my “father” inscribed in the list of German patriots who gave their life for the Fatherland.

Indeed it was not my father but his uncle, whose name my father recieved five years after his “patron” fell in Galicia, in 1915. My father’s story was different. He fled his “fatherland” in 1936 to Palestine, in order to save his life and returned to Germany twenty years later. He did not run away from European nationalism to end up with another one after all…

I think I will not wait another 36 years to visit this landscape of unfamiliar memories again. After all, it is a family affair of sorts.