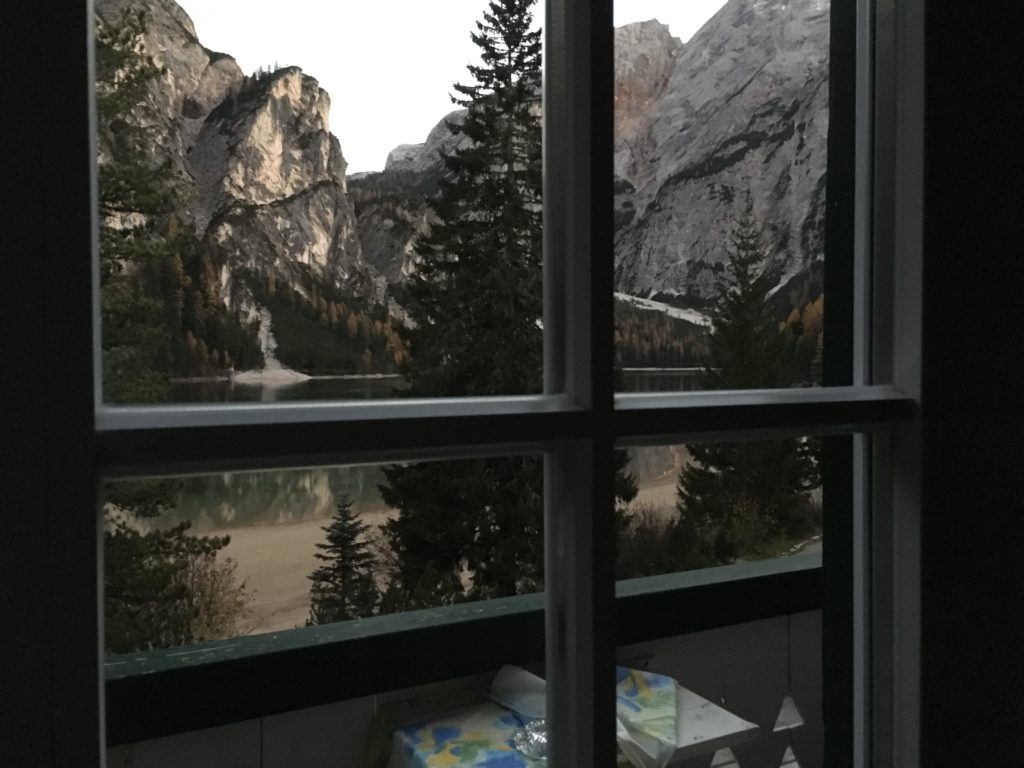

You read about the night on the WWI front line? The Dolomites offer more comfortable places to stay too. And stories of another war. Two days after the Biwak of Peace we found ourselves just at the other end of the same “national park”.

The “Hotel Pragser Wildsee”, a Grand Hotel at the shore of a mountain lake that couldn’t be more scenic and impressive, made history only in the last minute of the second war that turned the 20th century into a mess even more profoundly than the first one. Now even some of the brave Austrian and German soldiers of the first war were only considered as the “other” as such, Jews… Like Robert Rosenthal from the Hohenems family who fought for Austria in the Alps not far from here in 1917 and was taken to Auschwitz to be killed in reward.

But while the fronts along the peaks of the Dolomites experienced all brutal aspects WWI had to offer, the episode at Pragser Wildsee and the neighboring village Niederdorf that took place in the last days of April 1945 bordered on satire – or melodrama. Subject matter for a film that would provoke criticism about offering an “unbelievable plot” and “trivial kitsch”. The story in short – and with some distortion – one can read on a placque at the little chapel on the shore of the lake: here the Wehrmacht liberated 133 Nazi prisoners from the cruelty of the SS. Okay that’s not the whole story. We come to that.

In the staircase of the Hotel you can sit at a desk with a history. It belonged to Henning von Tresckow, a high ranking German officer who initially supported the Nazis, later joined the resistance – while he still was involved in war crimes of the Wehrmacht in Belorus. Tresckow tried to kill Hitler in 1943 and took part in the plot of 1944, making an end to his life when the coup failed. By that he became one of the heroes of the myth of a “Wehrmacht” that remained “honorable” during the war while only the SS was taken responsible for the Nazi crimes. Its just a few years ago that Rüdiger von Tresckow, his son, handed the desk down to the Hotel. Obviously a good place for myths.

When in the last days of the war high ranks of the SS and the Party were dreaming of the “Alpenfestung”, more then 130 prominent prisoners of the Nazis were still waiting for their “fate” to be determined in Dachau. The Nazis were preparing to retreat into their “alpine fortress” as a last chance to either fight a glorious never ending battle – or to negotiate some better outcome for themselves with the US-Army. For instance offering them to join forces against “the Russians”. The prominent hostages in Dachau seemed to be a valuable stake in this last gambling. So 133 of them were put on busses and taken south, into the Dolomites. In Niederdorf, in the Pustertal, the caravan came to an end. The “Hotel Pragser Wildsee”, the intended final stop, was occupied by a Wehrmacht unit. And the SS run out of petrol, a new destination was not in sight. So the SS troupe and their hostages got stuck. Confusion among the guards increased the tension but also enabled one of the prisoners to sneak out and get to a phone. It was Bogeslaw Adolf Fürchtegott von Bonin, a Wehrmacht officer who fell in disgrace in January 1945.

The hostages were a colorful mixture of prominence, politicians like the French president Leon Blum or the last Austrian chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg, activists of German resistance like Martin Niemöller and family members of von Stauffenberg and Goerdeler, foreign notables and German aristocrats, British intelligence agents but also former Nazis whose careers came to a dead end, like Hjalmar Schacht, the former minister of finance, or members of the Wehrmacht who at some point disagreed with Hitler or with other leading Nazis. Among them Franz Halder was probably the highest ranking officer, “Generalstabsschef des deutschen Heeres” (chief general of the German army), the mastermind behind the war against Soviet Russia and some of the criminal orders, paving the way to the war of racist and anti-Semitic destruction. A few weeks later Franz Halder would boast with reminding everybody that he belonged to a group of resistance in the Wehrmacht, that back in 1938 was opposing Hitler’s hurry to go to war, even being ready for a coup, now presentable as anti-Nazi “resistance”.

But in the last days of April 1945 it wasn’t time for that yet. The SS got uneasy and also more and more drunk as they had no idea where to take the prisoners – and the prisoners feared the worst. Von Bonin managed to get a line to the Wehrmacht in Bozen and asked for help. General Röttiger was not amused. He had other problems. Together with SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff, the SS leader in occupied Italy since 1943, he was organizing a separate capitulation in Italy – and how to save their heads in the times coming. A Wehrmacht officer, Wichard von Alvensleben, was sent to Niederdorf to check the situation. And also Karl Wolff, the high ranking SS-leader, now was keen to “help” von Bonin and the SS-hostages. In the end the SS troups had to leave the prisoners to the Wehrmacht and hurried to Bozen. And the 133 prominent hostages enjoyed the end of the war on the lake and waited for the American troops.

Franz Halder made a good deal. He served the Americans as one of their major consultants when it came to the history of the war. He wasn’t put on trial in Nuremberg and the Americans took care that also his regular “Denazification”-trial ended with acquittal. When the West-Germans prepared themselves for building up a new army – now as American allies – his interpretations of the war became the canon of myths forming the basis of the “tragic” image of the Wehrmacht: being abused by the demonic Adolf Hitler, struck by fate, or fighting a preventive war against the Russians. In any case, having “no choice”.

Karl Wolff, once the SS chief of staff behind Himmler, also made a good a deal – with the US army, starting in March 1945 and finishing the war in Italy already six days before May 8, 1945. But also after the war, when the Americans spared him from prosecution in Nuremberg, because they now didn’t want to disclose the details of their secret negotiations with him. About the crimes of the SS, the murder of Jews and others, he claimed to have learned only in 1945.

He became active for the advertisement department of an illustrated paper and intended to spend the rest of his life next to another lake, in Starnberg in Bavaria. But the last word wasn’t spoken yet. In 1964 he was tried and sentenced in Munich for complicity in murder in more than 300.000 cases, when his active participation in the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto and the deportation and murder of its inhabitants in Treblinka was publicly disclosed.

In 1969 he was released “for health reasons” and enjoyed the last fifteen years of his life, making friends with journalists like Gerd Heidemann from the “Stern” magazine – and with a notorious forger, Konrad Kujau. So the last “project” Karl Wolff was involved in, was the publication of the fake diaries of Adolf Hitler. When he peacefully died, a few weeks after his conversion to Islam, the forged diaries already had become the subject of a major scandal in Germany. But Wolff missed the trial that followed.

One of the “special prisoners” of the SS in Dachau was not taken to Pragser Wildsee but killed already two weeks before: Georg Elser, the brave carpenter, who tried to kill Hitler and his entourage in 1939, when it was time still to stop the war. He wasn’t prominent enough to make a deal about with the Americans.

We enjoyed the three days at Pragser Wildsee. We learned a lot.