He still deserves a rediscovery: the liberal intellectual and cosmopolite Moritz Julius Bonn. Born 1873 into a bankers family in Frankfurt and son of Elise Brunner from Hohenems he spent most of his childhood summers with his grandfather Marco Brunner in Hohenems. (His own father Julius Philipp Bonn died, when he was four.)

Moritz Julius Bonn became one of the most elaborate thinkers of free trade and liberal economy in the late German Empire and the Weimar republic – and a democrat by heart.

Bonn studied in London and became professor in Munich, before he spent three years of teaching in the US, from 1914 to 1917. His publications about the USA tried to foster understanding between Germany and the US, even during WW1, starting with “Amerika als Feind” (America as an Enemy) in 1917 and “Was will Wilson?” (What Does Wilson Want) in the same year, to the books “Die Kultur der Vereinigten Staaten” (The Culture of the United States) and “Prosperity. Wunderglaube und Wirklichkeit im amerikanischen Wirtschaftsleben” (Prosperity. Believing in Wonders and Reality in the American Economic Life) in 1930 and 1931 – but also in his seminal book “The Crisis of European Democracy” from 1925.

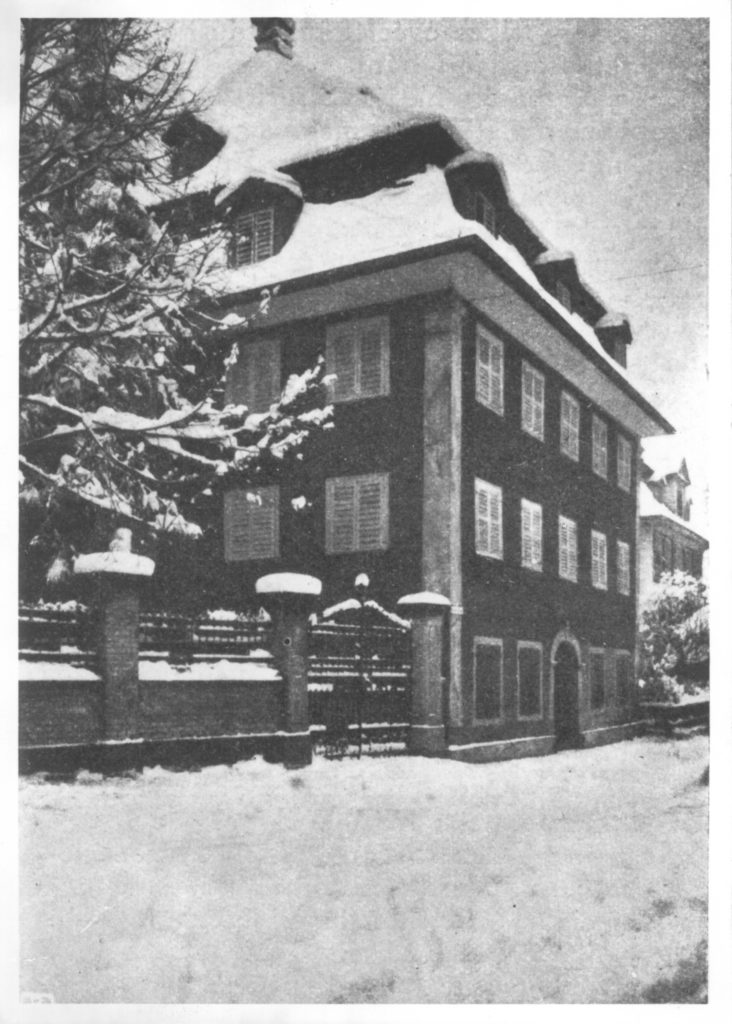

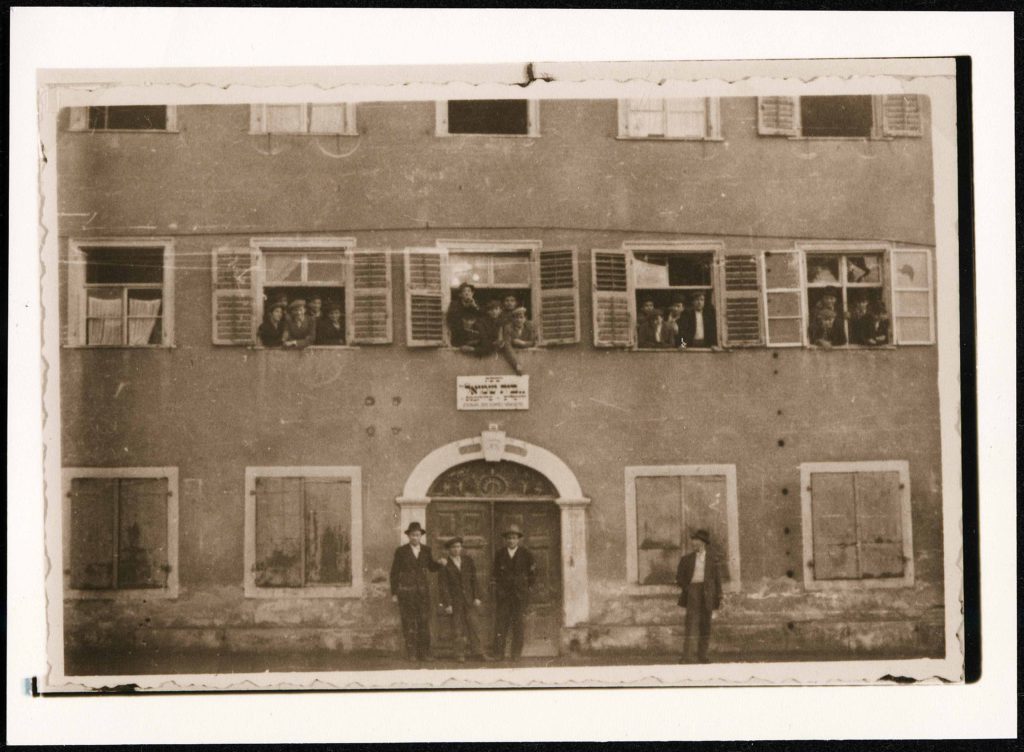

Moritz Julius Bonn now being the head of the Berlin University of Trade was fired in 1933 by the Nazis and emigrated to London. 1939 he started teaching in the US again for another seven years, but also advocating the US entering the war against Nazi Germany. Still he never cut his bonds with Germany and Austria completely. In his autobiography “Wandering Scholar” he did not only describe his life between the nations and political systems but also his childhood memories from Frankfurt and Hohenems. At that time he still – together with a few cousins – owned the Brunner House in Hohenems, that for time being, around 1950, served as a Talmud school for orthodox Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe. But now – on the day an american president starts to execute his war on free trade – lets listen to Moritz Julius Bonn, offering us an insight into the Hohenems he enjoyed as a child around 1880 – and how it informed his world views…

An Atmosphere Hostile to Customs

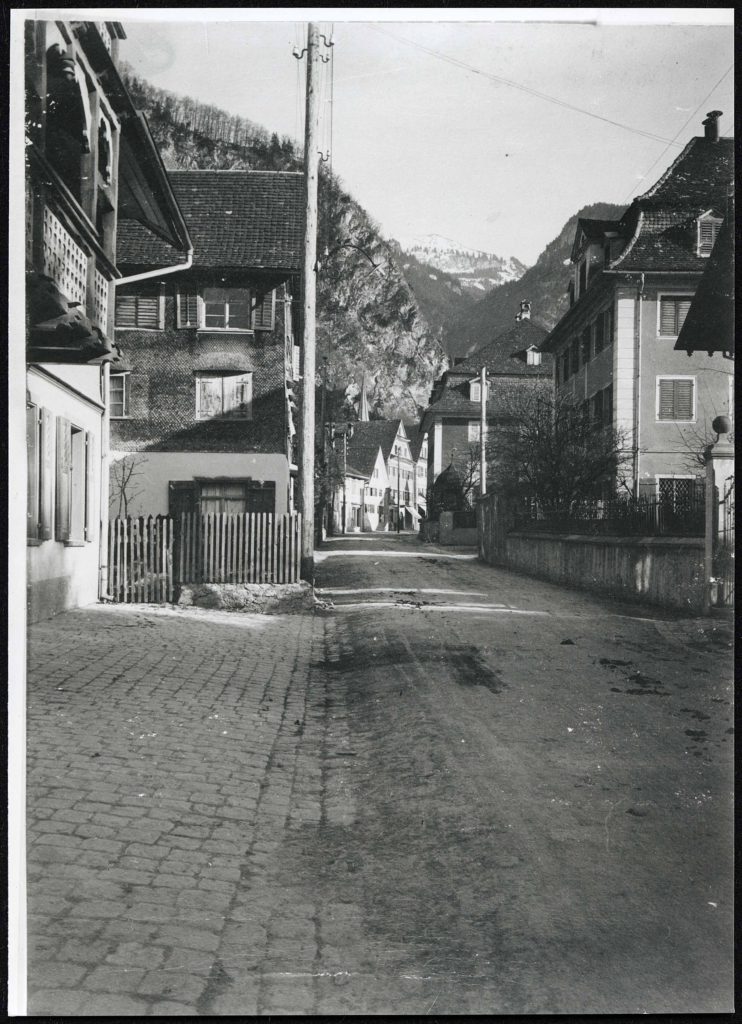

“The journey to Hohenems was inconvenient. It went via Stuttgart and Ulm to Lake Constance, and at that time took almost a day or an entire night: there were no sleeping cars on that stretch of the line. From Friedrichshafen the train went to Bregenz, where we passed through Austrian customs. In Austria the duty on sugar, coffee and the like was very high at that time. It was customary to smuggle a little sugar, coffee or embroidery in from Switzerland. With the many petticoats worn by the ladies, it was always possible to slip in an extra set without it making you conspicuous. I grew up in an atmosphere hostile to customs and I’ve never been clear in my own mind whether my attitude to free trade derived from this, or from textbooks about traditional national economics. The train journey from Bregenz to Hohenems took another hour. At the station we were greeted by Herr Weil, the porter, with a long, flowing white beard. He had such a kind smile that one of my little cousins once went straight up to him and asked: “Are you dear God?” Then we were packed into a roomy landau pulled by two ponderous white horses, and four weeks of bliss lay ahead of us.

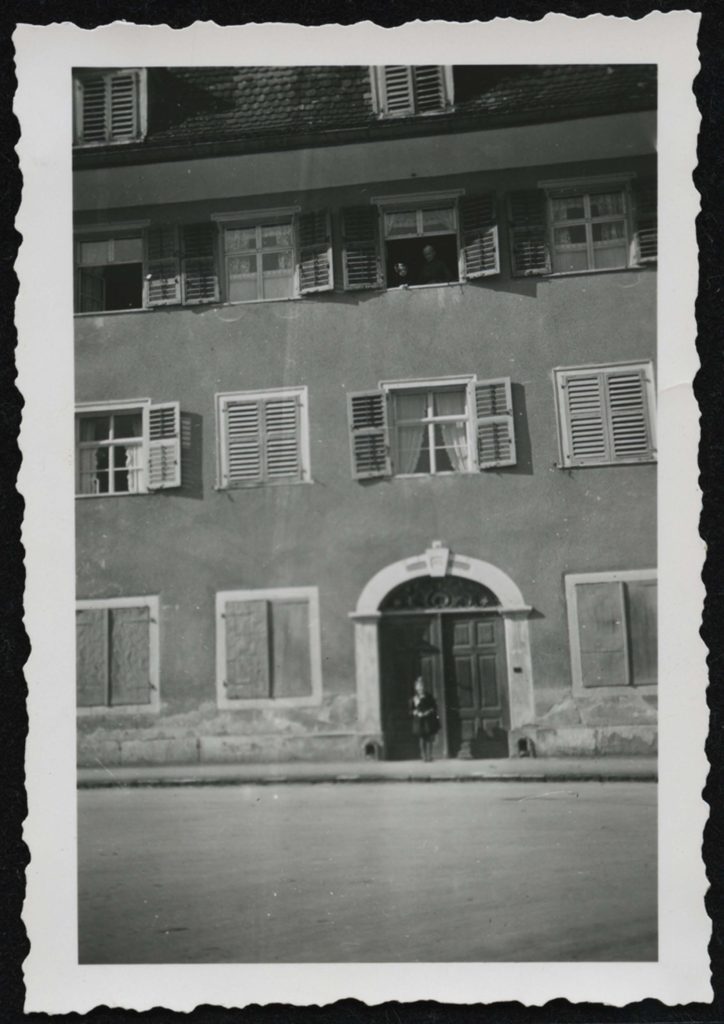

The Brunner house still stands on the main street of the town: before the rise of the Nazis it had been called Marco-Brunner-Straße after my grandfather. It was built in 1770, and looks like a superior townhouse, with three and a half storeys.

The highlight of the house was our playroom. It faced south and west, overlooking the courtyard and the garden. We had to go through the kitchen with its gleaming copper saucepans, and at least twice a week the smell of freshly roasted coffee wafted through. In Austria as it was then nobody talked about coffee beans. All coffee was coffee – with a little fig coffee and half a teaspoon of chicory added for flavor.

The playroom had a strawberry-colored tiled stove, and in its vents we cultivated silkworms. They needed an even temperature, and the greedy little creatures always kept us busy as we had to pick mulberry leaves for them. Grandmother had brought the love of rearing silkworms with her from her home town of Bolzano.

From the south-facing windows we looked out on the Säntis, the Churfirsten and the Drei Schwestern in nearby Switzerland; even on the hottest summer days the mountaintops were covered in snow. Behind the house there was a large square courtyard paved with cobblestones, enclosed on two sides by stables and the woodshed. Facing the street, there was a small front garden adjoining the house; on the west side was the start of a big orchard and vegetable garden, and a passageway covered with vines led to an arbor. Then there were meadows where a garden house with a beautiful garden room stood. That is where I used to put my first literary efforts down on paper.

Grandfather was a small-scale farmer. We kept a few cows that supplied the household with milk; butter and cheese we bought. We had enough hay for the cows and horses. Oats, bran and turnips had to be bought in. In the early spring Grandfather took on a couple of young oxen which were disposed of again in the autumn. In the courtyard, beside the woodshed – we had a little spinney – , the hens cackled and sometimes a few ducks waddled. An itinerant pedlar came regularly with a pack basket and brought us chicks, and every week a fisherman appeared carrying a small container on his back with live trout; we put them into the trough by the fountain, which bubbled day and night. Life was simple, but richly varied. The local shops made a poor impression, and delicacies were unobtainable.

The contrast to my life in Frankfurt could not have been more complete. Grandfather was not sociable and wanted to be left alone with his family. His only regular intercourse was his daily visit to a little café where he went after lunch – we ate at twelve – and played “tarock” (a card game using tarot cards) for an hour with old acquaintances.

The holidays in Vorarlberg strengthened my Austrian inclinations which memories of Frankfurt had aroused.

Grandfather hated the Prussians and particularly Prussian compulsory military service, like every good Austrian. He had spent the greater part of his working life in Switzerland and wanted me to emigrate there to escape the hated military conscription. I often went to St. Gallen, where my Uncle Luzian Brunner had taken over from my grandfather. There from my earliest youth on I had “living democracy” before my eyes. Of course I hated the playing at soldiers aspect of Prussian militarism. But in St. Gallen I learnt that the weapon can be a pledge of freedom, and does not have to be a tool of suppression. It often amused me when my north German friends discussed Austria or Switzerland from the viewpoint of summer holiday-makers. For many of them Swiss hotels and democracy were the same thing. The expertise of the Swiss hotel director of course made a deep impression on them. If ever someone somewhere were to want to set up a perfectly functioning socialist state, they would in fact be well advised to put it under Swiss hotel management.

The Jewish community in Hohenems had an elementary school which was highly reputed throughout the province. It was so good and so liberal that an administrative objection was required to close its doors to the non-Jewish population. (…) It is in itself a social disadvantage to belong to a small, unpopular religious community. However, the consciousness of being somehow different from most of your contemporaries offers a certain compensation. You are forced to look at nations and times from a broader perspective. It prevents you from letting yourself be swept along by the passion of the crowd that you would like to be part of, yet cannot quite be part of; but it gives you a kind of inner inviolability. You can easily break away from outmoded traditions and do not have to purchase personal freedom through breaking with the society you are born into; you see no obstacles in front of you that you might not have the strength to overcome; you do not hover between heaven and hell, between sin and salvation, and can become free without having to wear a martyr’s crown.”

From: Moritz Julius Bonn, So macht man Geschichte, Munich 1953, pp. 26-29. The slightly different English edition was already published four years earlier: Moritz Julius Bonn: Wandering Scholar, London 1949.

Postcript: The rediscovery of Moritz Julius Bonn is on its way. In 2015 the Hamburg Institute for Social Research organised an international conference “Liberal Thinking in the Crisis of the Epoch of World Wars: Moritz Julius Bonn”. We very much hope that the results will be published.