We are working on a library of descendants. Preparing ourselves for the Reunion in July this year we searched our files for the books of the Hohenems descendants – and we extend our collection. While we do this we look back into waht we found already, and from to time will share this with you. Let’s start with Stefan Zweig and his memoirs The World of Yesterday. Memories of a European, written in his years of Exile, before he committed suicide with his last companion Lotte Altmann in Petropolis, Brazil, in February 1942.

He had begun with this project in 1934, but was working on it seriously in the last years of his life, when he lived in Great Britain and then in New York (using the Library of Congress in Washington as a major source) and finally in Brazil. His remarks about his Hohenems family is full of irony.

This Kind of Nobility

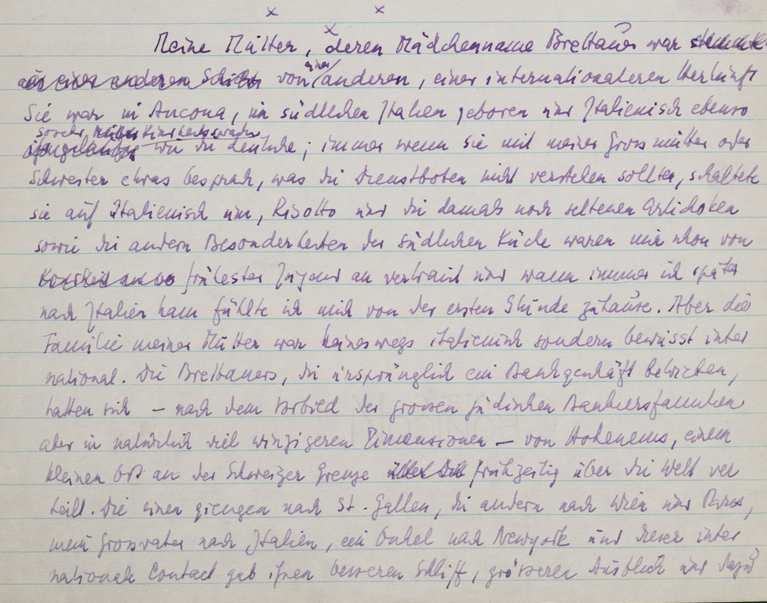

My mother whose maiden name was Brettauer was of a different, international descent. She had been born in Ancona, in southern Italy, and Italian was as much her childhood language as German; always when she was discussing something with my grandmother or her sister that the servants should not understand she switched to Italian. Risotto and artichokes which were still a rarity at the time as well as the other specialties of Mediterranean cooking were familiar to me from my earliest childhood, and whenever I later went to Italy, I immediately felt at home.

But my mother’s family were by no means Italian, rather they were consciously international; early on the Brettauers, who originally owned a banking business, had spread out across the world from Hohenems, a small place on the Swiss border – following the model of the great Jewish banking families, but of course on a much more modest scale. Some went to St. Gallen, others to Vienna and Paris, my grandfather to Italy, one uncle to New York, and these international contacts gave them more polish, a wider outlook, and a certain family arrogance into the bargain. (…)

As a large-scale industrialist my father was certainly respected, but my mother, though very happily married to him, would never have tolerated his relations being put on a par with hers. This pride in coming from a “good” family was ineradicable in all the Brettauers, and when in later years one of them wanted to show me special goodwill, he would say condescendingly, “But you really are a true Brettauer”, as if wanting to say in recognition: “You came down on the right side.”

This kind of nobility which many a Jewish family assumed on its own authority amused me and my brother even as children, and soon annoyed us too. Again and again we got to hear that these people were “refined” and those “unrefined”, enquiries were carried out into every friend to see if he came from a “good” family and checks were made down to the last detail about the origin both of his relations and their fortune. This constant classification which actually formed the main topic of every family and social conversation at that time struck us as extremely ridiculous and snobbish, because when it came down to it, in the case of all Jewish families, they had emerged from the same Jewish ghetto by only a matter of fifty or a hundred years earlier. (…)

It is generally assumed that becoming rich is the real and typical life ambition of a Jewish person. Nothing could be more wrong. For him becoming rich means only an intermediate stage, a means towards the true purpose and in no way the inner goal. (…) Even the wealthiest man will prefer to give his daughter to a desperately poor intellectual than to a merchant. (…) even the poorest pedlar dragging his wares through wind and bad weather will try to let at least one son study, making the most extreme sacrifices, and it is regarded as an honorific title for the whole family to have someone in their midst who is visibly highly regarded in the intellectual field, a professor, a scholar, a musician, as if he ennobled them all through his achievements.

From: Stefan Zweig, Die Welt von gestern. Bermann-Fischer Verlag, Stockholm 1944, pp. 23-25.

So very interesting

Thank you

Christine Angiel( Brunner Family)