Isn’t that a marvelous way to address your family, sending greetings and letters from South-East Asia to New York? Just don’t think of too much of decorum. With all these Kahns you better keep things simple.

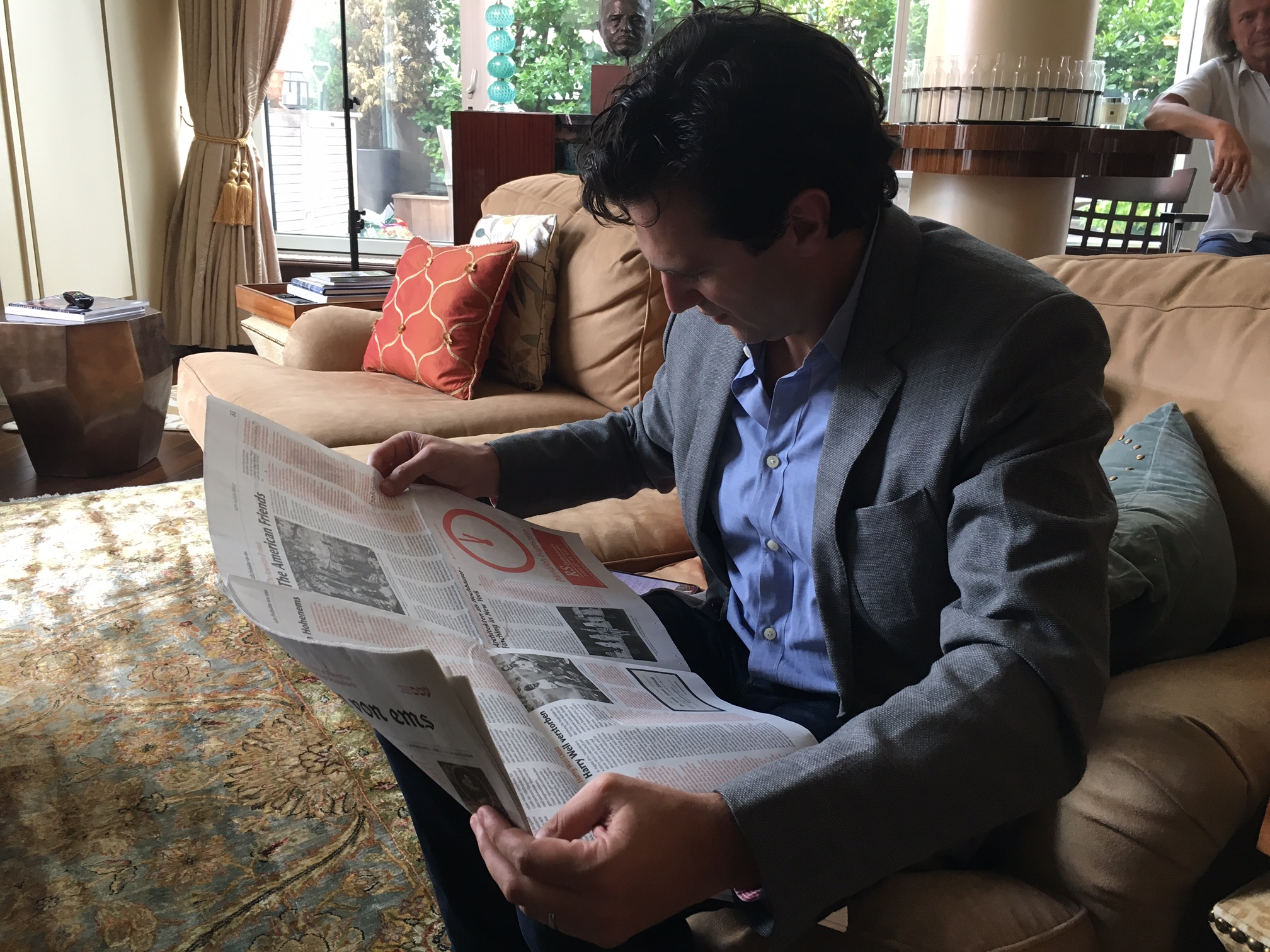

Meeting Ely Jacques Kahn III. (He is called Terry – for being the third) and his son Ely Kahn IV. in Terry’s New York apartment, full of memorabilia of their father/grandfather Ely Jacques Kahn Jr. and their grandfather/great-grandfather Ely Jacques Kahn, son of Jacques Kahn and Eugenie Kahn (both grandchildren of the same Jakob Kahn in Fellheim…) – can you still follow me? – one is tempted to join in by simply addressing them the “Kahns!” I am not going into the rest of the Kahn’s marriage policies. Growing up among all these Kahns from Hohenems and Fellheim (Bavaria) you better develop your sense of humor. And that’s what the Kahns did.

We are here in New York to shoot a film about Ely Jacques Kahn (EJK) the first, an eminent New York architect from 1920s to the 1960s. Born in Manhattan, he took part in shaping the city with his skyscrapers, from the early, set back loft buildings in New York’s garment district to the highrise towers of the 1950s and 1960s. “We” refers to Ingrid Bertel and Nikolai Dörler (working on a documentary for Austrian television), Ekkehard Muther and I, my own role loosely defined as consultant. It was wonderful: for once not experiencing the risk but only the nice side effects of a project. I highly recommend being a consultant.

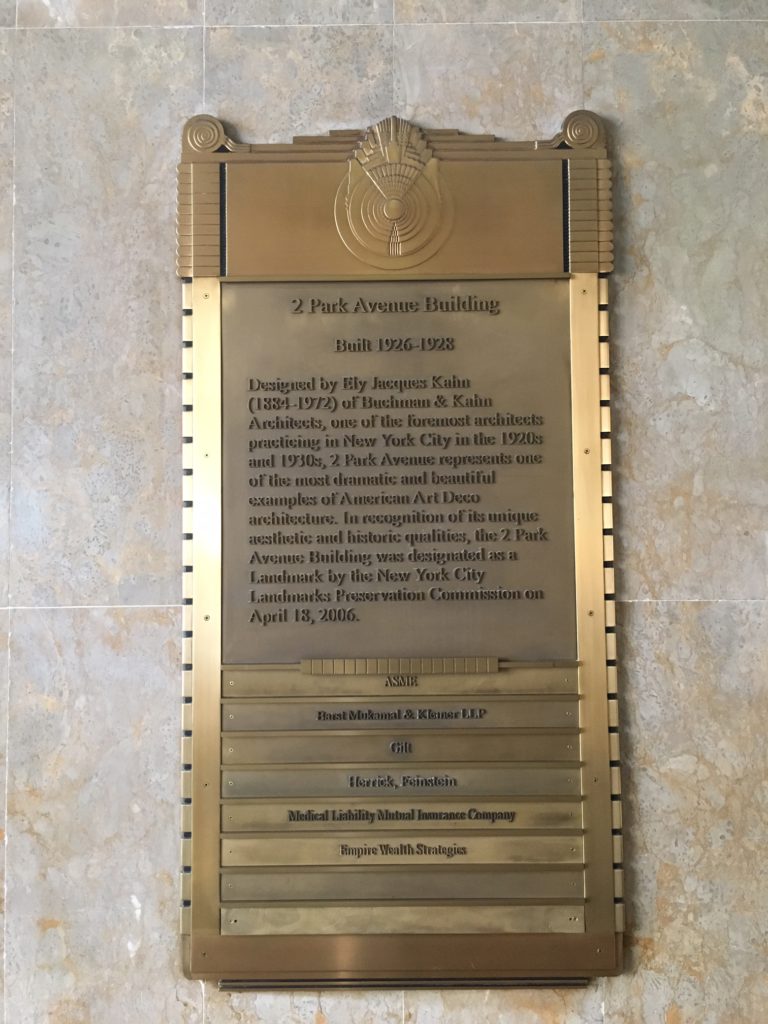

Kahn was maybe not the most celebrated among the modern New York architects. But he was definitely one of the most refined, successful and after all influential among them. He did not only most efficiently supplied the market with flexible and usable office space, he developed an elegant sense of detail and material that was outstanding. “No more copying!” he declared again and again, and fought against both the still flourishing historism and against a modernist attitude that used “international style” more as prop décor rather as a technique of finding practical solutions. From his training at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris and his close relationship with Vienna and the “Wiener Werkstätten,” he took the opportunity to collaborate in his firm with architects, artists and designers from all over the world, especially from Asia and Austria. He was keen to create an ornamental look though mostly abstract structures for facades and for the lavishly decorated lobbies and entrance areas, which offer a sense an abundance of attraction.

By 1901, EJK’s sister Rena had married Rudolph Rosenthal. For the next years the two of them would commute between Hohenems and Vienna. She studied art, and both of them amde friends with artists and designers in Vienna. In 1911, they moved back to New York, opening an art and design gallery on Madison Avenue, introducing “modern things” (as cousin Adele Kahn would call it) into the lifestyle of New York.

EJK also introduced the most advanced technologies into his buildings. In fact, he was the first to build an office building with air condition all over. Instead of playing around with metaphors of modernity (as other architects did mostly on public assignment), Kahn had the supply of the market—that is, the interests of the potential tenants of his buildings, mostly speculating on a growing demand for office space—a bubble that ended with the crash of the stock market in 1929. But that is another story. We come to that soon.

Sitting around the dining table with the Kahns—papers, books, sketches, manuscripts and letters spread all over—we grew fond of these “Kahns!” their understatement and witty irony, when it comes to the newly evolved interest in their (great-)grandfathers achievement. The documentary takes form, with diving into the family story, EJK III presents us with a smile. He tells us about how it was growing up in this bubble of an assimilated “non-Jewish” Jewish family, with Ely Jacques Kahn leading the Christmas celebration dressed as Santa Claus. Being Jewish, that meant—at least on the surface—not much much more than a sense of family and some experiences with a persisting discrimination, even in the American society. One family member belonged to a Jewish country club (other country clubs did not accept Jewish members still in the 1930 and 1940s). Another family member would not be accepted, as EJK Jr. recalled, on the editorial board of the Harvard Crimson, because the “quota” for Jews had already been reached.

However successful one was able to mingle professionally, in Ely Jacques Kahn’s generation, one still married other—equally assimilated—Jews, became member of the Ethical Culture Society (a non-religious but still mainly Jewish organization that tried to develop a secular set of rituals, philanthropy, schools and networking), or in general cultivated a social sphere based on shared experiences and backgrounds.

Adele Kahn (EJK’s cousin) named her autobiographical records “All about All of us.” She worked them together with Joan Kahn, EJK’s daughter, which was ironical rather than immodest I guess. EJK Jr. also fought his father’s autobiographical manuscript, which he tried to prepare for publication. But unlike Adele, Ely Jacques Kahn did not give anything personal away in his rather dry account of his professional career.

Still, when Terry gave this manuscript in my hands for the archives of the Museum I was overwhelmed by the trust in this gesture.

It seems that Ely Jacques Kahn remained—and still remains—a bit of a riddle for everybody in his family. Looking at the family photos after 1945 he often carries a mild smile that can suggest a lot. Having prominently shaped the face of the “capitol of the 20th century” (having learned what’s necessary in the “capitol of the 19th century”—Paris) he also knew that his success resided on the edge. His firm was cut down to a small portion of its original size when the depression demanded its toll after 1929. And more serious, the “events in Europe” cut into the heart of the family, when after 1945 it became clear that his sister-in-law, Clara Rosenthal had vanished in the Holocaust, as so many more or less distant relatives were murdered in the camps.

That was obviously nothing to talk about, not even in the family. But there are things you communicate with each other even if you remain almost silent. “My sister is hopelessly lost,” Rudolph Rosenthal ended a letter to a friend of the family in November 1945. “This is all the News for today. Love from all!”

Kahn’s business though went up again after 1945. A new building boom in New York now asked for a new language of architecture. One of the last projects Ely Jacques Kahn was involved with was the Seagram Building that was designed by Mies van der Rohe – and was made possible by Ely Jacques Kahn’s skills. But looking on Kahn’s projects already developed during the last years of the war, the new spirit of a pure geometry of volumes and surfaces is clearly visible.

Talking with the Kahns is somewhat also reading between the lines. EJK Jr., in his own autobiographical diary, written in 1972, gives a rather amusing account of instances in which he was interviewed about his father. In the end of on of these talks a young man asked him, the eminent journalist (who wrote for “The New Yorker” for forty years), what he would have done differently if he were the interviewer. “I would have taken notes,” EJK Jr. drily responded. But making notes, I feel that strongly, is also writing between the lines. As in so many families…

In the end of our interview (everything safe on tape anyhow), EJK III had a better advice for us: Let’s meet in the Harvard Club on 44th Street tonight and have dinner on the roof top. We all enjoyed that evening very much.

Now, while I am writing this, Ingrid and Nikolai are finishing the film “Hohenems-Manhattan. Die Wolkenkratzer des Ely Jacques Kahn” for Austrian television, to be aired on September 18. I can’t wait to see its premiere in the Salomon Sulzer auditorium in Hohenems a day before at 6pm.