A week ago I visited family in Frankfurt. There is not that much left of it, but apart from family there are still a lot of friends. Some of them, a family who I’ve known for more than 30 years, took me and my wife on a stroll to the latest “must see spots” of the city.

The European Central Bank is located by the riverside at the Frankfurt East End. There are open air cafés and youth sports grounds along the river, signs of the gentrification of an area that was once the heart of Frankfurt’s industry, transportation and storage in grand scale. Skate board enthusiast find refuge there, as does but anybody who wants to chill out, stroll around, or look for expensive housing.

Coming back to my friends, I know both of them from student politics. They became a family on their own, a little before I did the same. And their professional lives went to different direction from mine. Law, public finance, and business. A bit of another world. And still we never lost sight. We’d known each other 10 years when I learned of her family’s Jewish background, more by chance than by intention. It was not a subject to carry along in front of you. But it explained the mutual understanding of one or the other sensitive subject we’d had since we knew each other.

Some 20 years ago, my friend discovered her connection to the family named “Hohenemser,” that settled in Mannheim, founded a bank and partially moved to Frankfurt later. My friend is not a “descendant” herself. In Felix Jaffé’s genealogical universe—the one he introduced me to when I moved to Hohenems 12 years ago—she is something like a “very distant cousin.” When my friend got a huge genealogical collection of family charts from her mother, the frequency of the name “Hohenemser” made an impression on her. They became regular visitors in Hohenems.

This time, though, we were in Frankfurt. They took us on the promenade along the river—that so much informed my own childhood experiences—as well as the Main and its harbor.

The European Central Bank is a masterpiece of a skyscraper, following the deconstructionist design of the Coop Himmelblau architects from Vienna. It’s located right next to the former and truly giant Market Hall. The Frankfurt Market Hall was an icon of modernity in itself, built in 1928 by Martin Elsässer and functioning til 2004, when it became part of the future European Central Bank complex, which finally opened last year.

But there was a time when the Market Hall was not only delivering food— fruits, vegetables and meat to Frankfurts grocery shops—but human cattle for transport to the East. From October 1941 until February 1945, the deportations of Jews from Frankfurt to the camps and Ghettos began here in the market hall, where the deportees had to assemble in the basement of the building and wait of their transport. A number of “very distant cousins” of the “Hohenemser” and other Hohenems families started their last journey from here. (The Jaffés, Felix’s Frankfurt-based part of his family already had left the town in the 1920s).

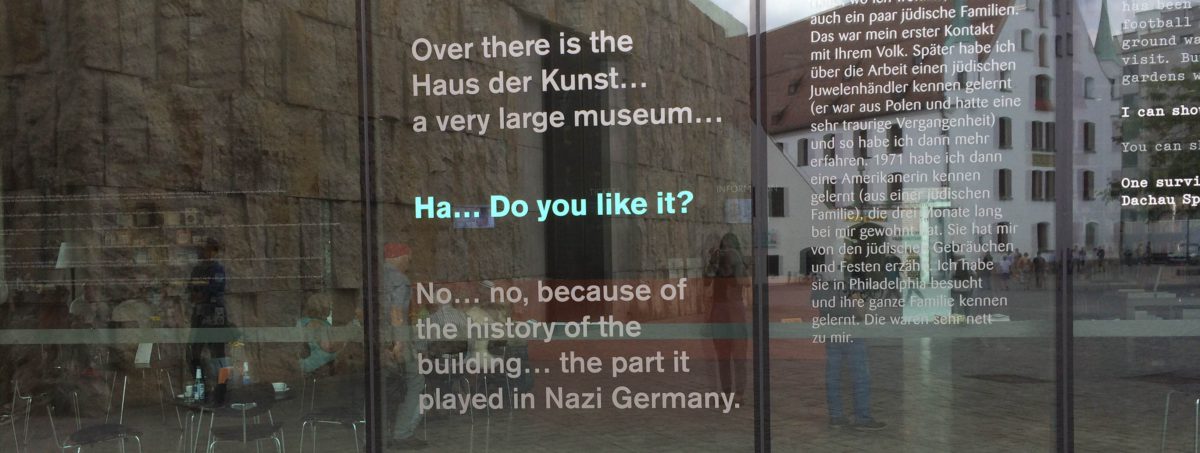

Last year—the same year the European Central Bank building opened—there also opened a memorial that reaches from within. Due to ECB security, visitors can only enter with special permits and elevated security standards, but passerby are drawn to the environment of the building and the story with inevitable curiosity. “What is written there?” a little girl asks her father as we walk by. To my disappointment, I was not able to follow their family discussion. I am a curious person, that’s one of my “deformations professionelle”—or the other way round: one of my weak points that put me on the track of museums.

I took a few photos of the outside portion of the memorial and the awesome scenery around it that puts everybody in a time machine between modernity, catastrophe and post-modernity with all its playfulness and contradictions. And then we went to a little boat house in a once proletarian swim club between the bushes (literally) and forgot about modern life.